Broadened and Culturally-Inclusive View of Science

SCIENCE: shared through stories

SCIENCE: shared through stories

In Integrative Science, by choosing to understand that we use stories to share our science knowledge, we are enabled to acknowledge our own agency within our knowledge systems.

Our use of story further serves to remind us that ontologies, epistemologies, methodologies, and goals play key roles in the assemblage of science stories in all cultures and worldviews. These can and do vary among different cultures and worldviews.

We believe it critically important today that we know the specific ontologies, epistemologies, methodologies, and goals of the sciences that influence our lives, frame our societal decisions, and are taught to our young.

In Integrative Science, we acknowledge and understand that the Indigenous and Western sciences have different ontologies, epistemologies, methodologies, and goals.

Read more: Bartlett et al. (authors' final revised draft for chapter in forthcoming book)

Integrative Science research to highlight the philosophies – ontologies, epistemologies, methodologies, and goals – in our science stories

It was early in our Integrative Science journey when we realized that participants need to be able to place the actions, values, and knowledges of their own culture out in front of themselves like an object, to take ownership over them, and to be able to say "that's me". And, as guided by Two-Eyed Seeing, we need these "objects" for both the Indigenous and Western worldviews. In this way, participants can learn both "that's me" and "that's you" to foster working together.

Thus, we have chosen to emphasize four "big picture" philosophical questions, namely those about epistemology, ontology, methodology, and goals. And, we have developed simple responses (in text and visual form) for these questions.

The questions in four areas of philosophy and our simple textual and visual responses are provided below.

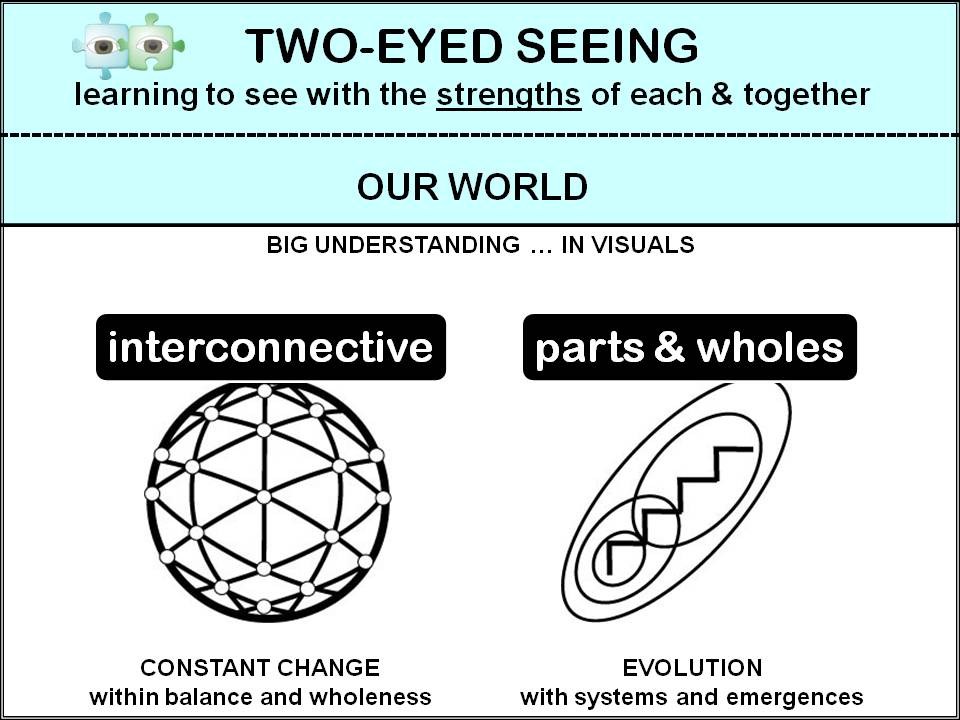

1. Our World: This relates to ontologies, as we share a desire for our knowledges to have an overarching understanding of "how our world is", while at the same time there may be differences as to what we deem these to be.

Our "big pattern" question here is: What do we believe the natural world to be?

A possible response from within Indigenous science is: beings ... interconnective and animate … spirit + energy + matter …with constant change (flux) within balance and wholeness.

A possible response from within Indigenous science is: beings ... interconnective and animate … spirit + energy + matter …with constant change (flux) within balance and wholeness.

A possible response from within Western science is: objects ... comprised of parts and wholes characterized by systems and emergences … energy + matter … with evolution.

The visual we created to complement these words is seen above.

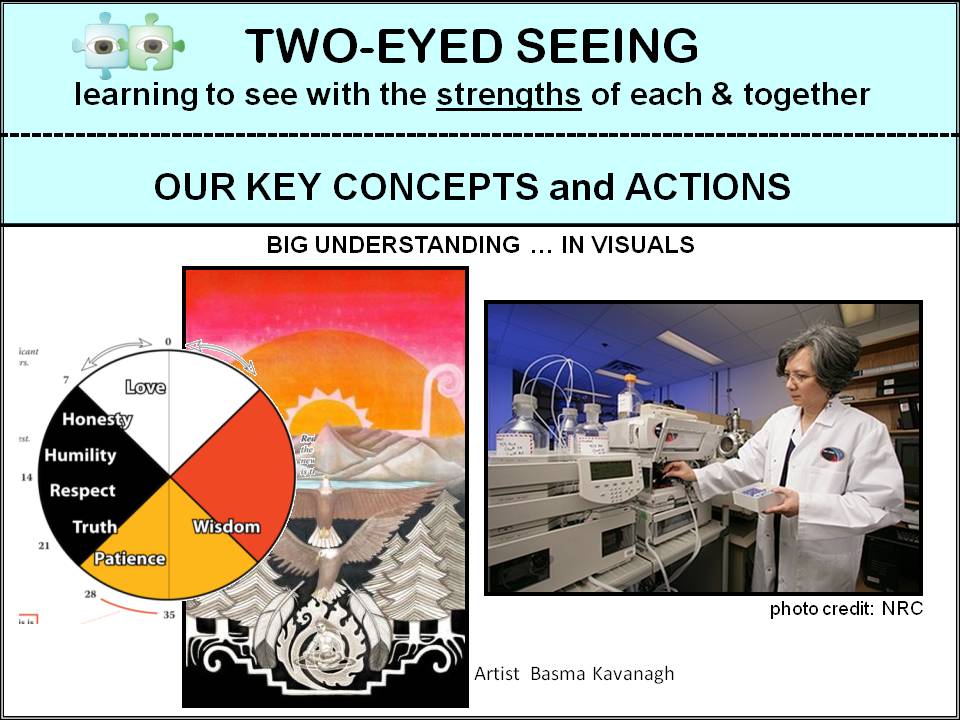

2. Our Key Concepts and Actions: This relates to epistemologies, as we share a desire for our knowledges to observe key values while at the same time there may be differences as to what we deem these to be.

Our "big pattern" question here is: What do we value as "ways of coming to know" the natural world, i.e. what are our key concepts and actions?

A possible response from within Indigenous science is: respect, relationship, reverence, reciprocity, ritual (ceremony), repetition, responsibility (after Archibald 2001.

A possible response from within Indigenous science is: respect, relationship, reverence, reciprocity, ritual (ceremony), repetition, responsibility (after Archibald 2001.

A possible response from within Western science is: hypothesis (making and testing), data collection, data analysis, model, and theory construction.

The visual we created to complement these words is seen above.

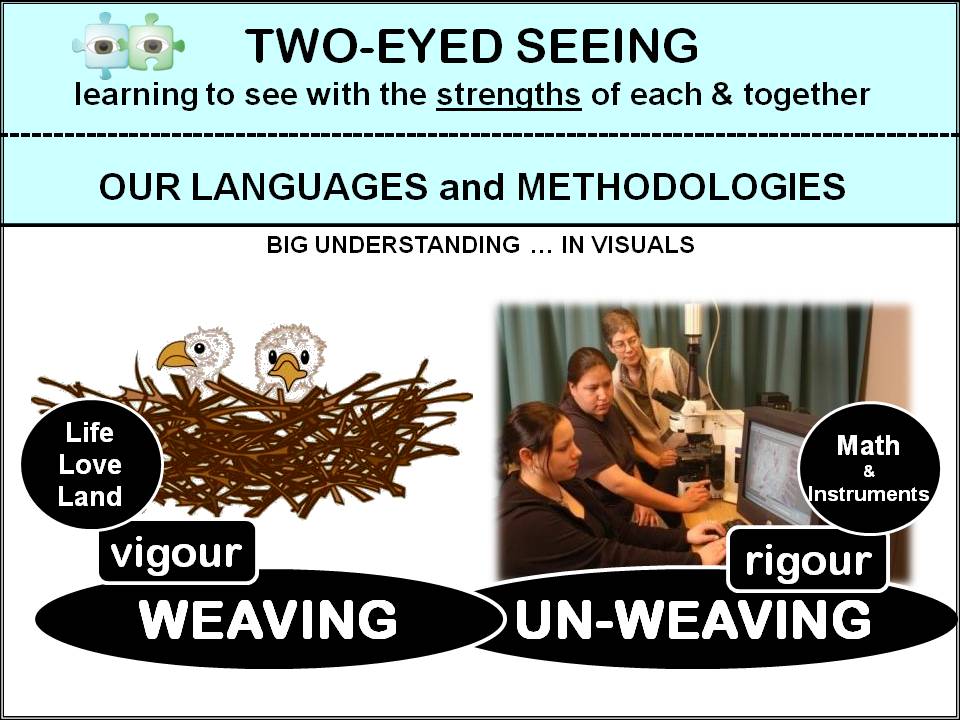

3. Our Languages and Methodologies: We can focus on core concepts for the languages and methodologies that structure our knowledges, as we share a tendency to want core concepts, while at the same time there may be differences as to what we deem these to be.

Our "big pattern" question here is: What can remind us of the complexity within our ways of knowing?

A possible response from within Indigenous science is: weaving of patterns within nature's patterns via creative relationships and reciprocities among love, land, and life (vigour) that are constantly reinforced and nourished by Aboriginal languages.

A possible response from within Indigenous science is: weaving of patterns within nature's patterns via creative relationships and reciprocities among love, land, and life (vigour) that are constantly reinforced and nourished by Aboriginal languages.

A possible response from within Western science is: un-weaving of nature's patterns (especially via analytic logic and the use of instruments) to cognitively reconstruct them, especially using mathematical language (rigour) and computer models.

The visual we created to complement these words is seen above.

4. Our Overall Knowledge Objectives or Goals: We can focus on objectives or goals, as we share a desire for our knowledges to have overall purpose while at the same time there may be differences as to what we deem these to be.

Our "big pattern" question here is: What overall goals do we have for our ways of knowing?

A possible response from within the Indigenous sciences is: collective, living knowledge to enable nourishment of one's journey within expanding sense of "place, emergence and participation" for collective consciousness and interconnectiveness … towards resonance of understanding within environment … towards long-term sustainability for the people and natural environment (tested and found to work by the vigourous challenges of survival over millennia).

A possible response from within the Indigenous sciences is: collective, living knowledge to enable nourishment of one's journey within expanding sense of "place, emergence and participation" for collective consciousness and interconnectiveness … towards resonance of understanding within environment … towards long-term sustainability for the people and natural environment (tested and found to work by the vigourous challenges of survival over millennia).

A possible response from within the Western sciences is: dynamic, testable, published knowledge independent of personal experience that can enable prediction and control (and "progress") … towards construction of understanding of environment … towards eventual understanding of how the cosmos works (tested and found to work by the rigourous challenges of experimental design).

The visual we created to complement these words is seen above.

Our simple depictions of answers to questions in the four key philosophical areas enable us to put the philosophical considerations for our knowledge systems out in front of ourselves like an object (tool). In the Spirit of the East, we believe such can help encourage "our place of beginnings" towards the thought frameworks that Ermine's (2007) insight indicates are required to reconcile the solitudes of Indigenous and Western cultures. We suggest that the first phase of entering ethical space for the purpose of reconciling our scientific knowledges and ways of knowing – the ethical space conceived within Ermine's insight – includes learning to appropriately, correctly, and respectfully acknowledge the "that's me" and the "that's you" of our worldviews, as they configure our sciences.

In having developed these simple depictions, we emphasize that our approach is intended to help orient within "our place of beginnings". While having done this, we also concur strongly with Watson and Huntington (2008) that the "intellectual traditions we assemble, 'Western' and 'Indigenous,' are not entirely separable into our individual selves, who are instead a 'multiplicity of multiplicities' ."

Weaving Capacity: As indicated for co-learning, we need weaving capacity – the ability to weave back and forth between our cultures' actions, values, and knowledges, i.e. between our ontologies, epistemologies, methodologies, and goals – as circumstances require. We believe our simple textual and visual depictions of key philosophical understandings help in this regard. In the words of Integrative Science Research Fellow Dr. Marilyn Iwama: "We are learning to weave back and forth between our knowledges, our worldviews and our stories. We are learning to navigate that weaving by recognizing patterns that help us do that. Call those patterns knowledge orientations. Call them maps – maps for the garden. We have learned the importance of making our knowledges, our stories, visual."

With an ability to weave back and forth, participants in the Integrative Science journey are better equipped to recognize and avoid a situation that could otherwise develop a clash between knowledges, a domination by one worldview, or assimilation by one worldview of the knowledge of another. Both co-learning and Two-Eyed Seeing require this weaving capacity.

Integrative Science research to explore story

Storytelling is something we explore within Integrative Science research, as it is of significant interest to Elders, educators, and many others on the Integrative Science journey. In this regard, we wish to remind ourselves of the guiding words of Mi'kmaw Elder Albert Marshall: "Story is the foundational basis of all relationship". We also acknowledge the work by Archibald (2008) and Smylie (2004) for their research insights about story and its importance in knowledge systems.

Archibald's (2008) book "Indigenous Storywork; educating the heart, mind, body, and spirit" explains that she worked with Coast Salish and Stó:l? Elders in British Columbia to learn how Indigenous oral stories both nourish knowledge systems and are knowledge systems. She explores seven principles (respect, responsibility, reciprocity, reverence, holism, interrelatedness, and synergy) of "storywork" in her effort to find a respectful place for stories and storytelling in contemporary education.

Smylie (2004) indicates: "In Indigenous knowledge systems, generation of knowledge starts with 'stories' as the base units of knowledge, then proceeds to 'knowledge' as integration of the values and processes described in the stories, and finally culminates in 'wisdom', a distillation of experiential knowledge. This process can be viewed as cyclical, since keepers of 'wisdom' in turn generate new 'stories' as a way of disseminating what they know."

References for above:

Archibald, J. (2001). Editorial: sharing Aboriginal knowledge and Aboriginal ways of knowing. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 25(1), 1-5).

Archibald, J. (2008). Indigenous storywork; educating the heart, mind, body, and spirit. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

Ermine, W. (2007). The ethical space of engagement. Indigenous Law Journal, 6(1), 193-203.

Smylie, J. (2004). Health sciences research and Aboriginal communities: pathway or pitfall? Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 26(3), 211-216.

Watson, A., and Huntington, O.H. (2008). They're here – I can feel them: the epistemic space of Indigenous and Western knowledges. Social & Cultural Geography, 9(3), 257-281.